#Industry (Production, process)

Ceramic Air Valves Never Fail

Multiple daily failures of valves in a smelting operation’s cranes led to a switch to ceramic valves, which have so far delivered 100% reliability and significantly lowered costs.

The guys in the pot rooms love the reliability and strong operation of the new air valves because the jackhammers are more powerful and work every time.”

This is a quote from the Operations Superintendent of Noranda Aluminum, New Madrid, Mo. Until recently, air-valve failures were a daily occurrence at this mill, costing thousands of dollars per day in parts, labor, and lost production. Today, the problems have disappeared, going from 60 failures per month to zero in one application.

The situation

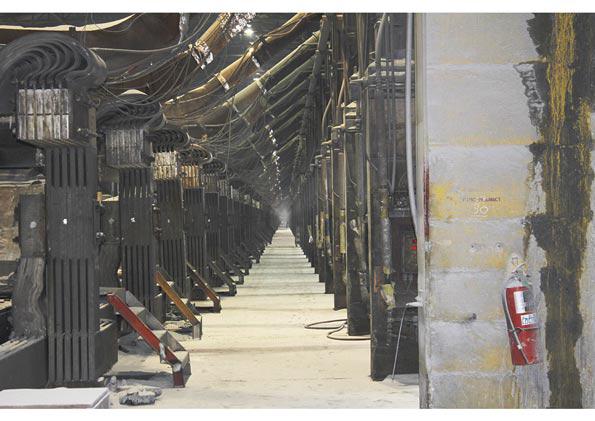

Shown is a pot room in Noranda Aluminum’s smelting operation. Click on image for larger view.

Noranda Aluminum is a large smelting operation situated on the Mississippi River in southern Missouri. The plant uses alumina oxide to produce quality aluminum for the industry. The raw product comes in on barges and is off-loaded and conveyed to the mill, where it’s turned into pure aluminum. The final product then gets shipped to different regions of the country, where it’s used to make car parts, foil, and other everyday products.

Producing aluminum from the ore is a detailed and costly process, and a lot must happen between the ore barge’s arrival and when the trucks leave the mill’s shipping docks. It requires the use of large and complicated equipment, heat, chemistry, manpower, and a huge amount of know-how. The aluminum is produced in large pots that are heated to a high temperature. Here the alumina oxide is mixed with other elements and chemicals, heated, and carefully blended into molten aluminum.

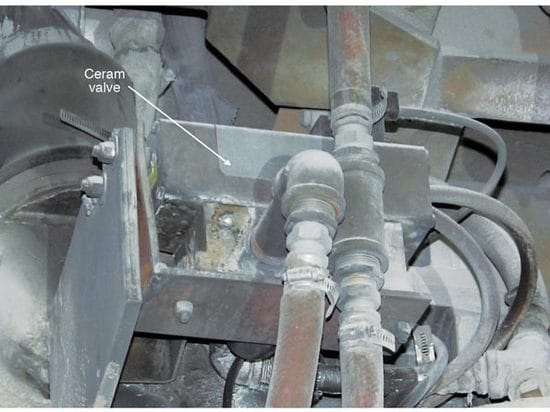

The crane’s pneumatic jackhammer breaks the crust that forms on top of smelting pots.

A hard crust forms on top of the pots during this process. This crust must be broken periodically so anodes made of carbon can be exchanged. These electrodes, through which positive electric charge flows, create the heat that melts the ore. These are consumed in the process and must be replaced with new elements on a periodic schedule.

A critical apparatus used to replace the anodes is a crane that functions as a crust breaker. The crane’s pneumatic jackhammer—raised and lowered by an air cylinder—is used to break the crust. Compressed air powers both the cylinder and jackhammer. Maneuvering them requires a solenoid-operated directional control valve.

The problem

For years, the directional control valve was a major problem for the mill. When it failed, the jackhammer became inoperable, resulting in a crisis situation. A repair crew was called immediately to manually lift the jackhammer out of the molten aluminum so that it was not destroyed. After that, the air valve was either replaced or repaired, enabling the crane to be put back into service.

The old valves caused multiple failures every day.

To understand the magnitude of the problem, it’s helpful to explain that Noranda’s New Madrid smelter has 348 pots on its #1 line, all making aluminum 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Eight cranes with jackhammers perform the crust-breaker function for all 348 pots. It’s a continuous process, and to have a crane with its jackhammer down due to a failed air valve turns into an enormous and costly problem. In the past, each crane broke down at least three or four times a day due to a failed valve. This cost the plant $5,000 to $6,000 every day in parts and labor, not including lost production.

Alumina oxide is taken into compressed air, which jammed the old valves.

Valves fail primarily from high contamination of the compressed air. The raw products of alumina oxide and fluoride are taken into the compressed-air system and delivered to the valves. These products are abrasive, corrosive, and found in abundance throughout the plant. But that’s just part of the cause of contamination.

South Missouri along the Mississippi River has a hot and humid climate. That means the compressed air carries a high level of moisture nearly year round. To make the situation even worse, the plant is more than 40 years old, with compressed-air lines producing pipe scale that ends up in pneumatic components. The pipe scale alone can make ordinary air valves fail regularly.

Due to the volume of air used, the high contamination levels, and the compressors being on board the crane, filtering the air becomes impractical due to high cost and added maintenance. Although air filtration was tried, the maintenance crews found the air filters clogged up quickly and became inoperable in short order. The extreme contamination makes it virtually impossible to filter the air economically.

The answer

B. J. Burks, the maintenance supervisor over the pot lines, was looking for a solution. He tried different internal valve materials and configurations, special seals, and air filtration in an effort to enhance valve performance. None of these worked out. Then Burks found an air valve made by AVENTICS Corp. (formerly Rexroth Pneumatics) that uses an entirely different technology from other air-valve manufacturers. This valve does not use a spool or a poppet, but rather sliding ceramic plates to control the air flow direction.

The Ceram valve uses sliding ceramic plates to control the air flow direction, allowing it to operate in harsh conditions.

The ceramic plates offer many advantages over spool valves. Because ceramic material is very hard, contamination has no effect on the plates. The design uses two ceramic plates placed one on top of the other. A ceramic-to-ceramic seal is formed where the plates fit together, thus eliminating any clearance for contamination to lodge like that found in spool or poppet valves—and ultimately avoiding jamming.

Contamination passes through large slots in the ceramic plates and is either delivered to the cylinder or exits through the valve exhaust ports without getting a chance to jam the valve. On top of that, there are no elastomeric seals in the critical area of the valve to wear or become damaged by the contamination. The combination of ceramic plates, a ceramic seal, and an extra strong return spring makes for a very robust valve that will operate reliably under the most contaminated conditions.

Under AVENTICS’ Discover the Ceramic Advantage Free Valve Program, Burks received for free a 1-in., ported single-solenoid Ceram valve to try out. His goal was to reduce some of the failures that cause so many problems. Burks thought if he could find a valve that would work for two or three days without failing, it would immensely improve his difficult situation.

After one week of operation, Burks was asked how the valve was performing. He replied, “Doing great and firing on all cylinders.” After two weeks he was asked again how the valve was running. He said, “Like a good watch.”

By this time, Burks knew he had found the solution to his problem. The AVENTICS Ceram air valve was performing as promised. The ceramic-plate technology survives the contamination, survives the heat, and withstands the harsh and abusive conditions inherent on the pot lines. He began replacing all of the jackhammer valves with the Ceram valve, completing the task after two weeks.

Impact and implications

Since switching to the Ceram valve, performance improved from many failures per day on the old valve to zero failures in the six months since the new valve’s installment. The company is enjoying very large cost reductions not only from the labor savings, but from the elimination of valve replacement costs. Ceram valve cost is 70% less than the previous valve, and valve repair costs are a thing of the past, too.

Ceram pneumatic directional-control valve features and benefits:

• Eliminates downtime because they don’t stick

• Saves air and money with tight shutoffs

• Overcomes design limitations of other valves

• Extended life of 150 million cycles, even in harsh conditions

• World standard ISO mounting

Production is up, which makes everyone happy. Because the Ceram valve has yet to fail, maintenance teams are now free to engage in preventive, predictive maintenance instead of reactive maintenance, which is a very important goal for Burks and his team. This helps keep the plant running more efficiently, reduces costs, and improves morale of the maintenance teams. Morale is up also with the crane operators. They say their jobs can be done more efficiently, because the cranes no longer need to be taken out of service thanks to the Ceram valves, which work every time.

Burks was asked if he could describe in one word the biggest benefit the Ceram valve has brought him so far. He thought for a moment and said, “Reliability. Reliability of the cranes has improved significantly. The result was immediate. This is big, real big. It means less downtime, more uptime, and higher equipment availability to the process. The cranes are much more productive now that they have air valves that do not fail. The payoff is huge. Labor costs are down. Maintenance time is down. Material usage is down. Overall productivity has improved. Performance and uptime has greatly improved and there is less waste of material. “

He mentioned another key component in making the change to the Ceram valve: Availability is very important. The old valves have a long lead time. Even delivery of repair parts can be difficult. Motion Industries’ local AVENTICS distributor has the Ceram valves in stock, making for quick delivery day or night.

Burks has already identified other areas of the plant that can benefit from the Ceram valve. Conditions may not be as harsh, but the payoff comes from the high lifecycle capability of the valve. One of the many features, as stated in the AVENTICS catalog, is an expected service life that exceeds 150 million cycles. In fact, it has been known to reach 400 million cycles. The end result is fewer air valve failures, less replacement costs, reduced downtime and higher productivity.

Overall, Burks’ maintenance team is experiencing less reactive maintenance and enjoying more time for preventive and predictive maintenance, which makes for a more productive mill.